TET’s recently acquired drone is keeping a watchful eye on vulnerable young plants.

TET-supported projects have surpassed 300,000 plantings. Yes, you read that correctly—over 300,000 eco-sourced plants grown in local nurseries, 300,000 volunteers’ spades to dig the holes, and that many cups of tea and biscuits too!

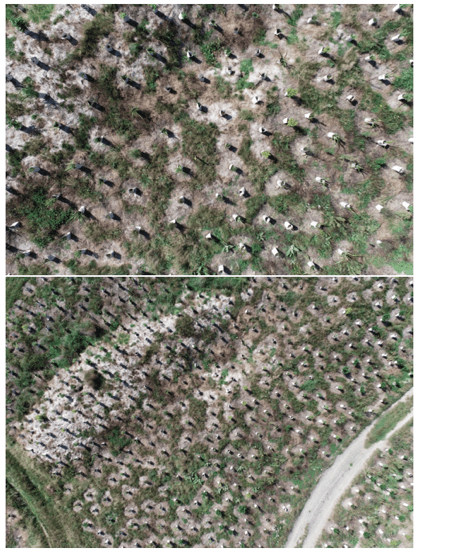

With such enthusiasm and willingness for community action, it’s important we know all this good work is bearing fruit. We want to verify the plants are surviving. With TET’s new drone, our supported projects are now able to monitor survival rates more efficiently and with greater accuracy.

This isn’t just good news for volunteer morale. It also allows funders to know their resources have been well placed.

Why drones matter

In the olden days, project managers and volunteers had to walk through their plantings, counting the number of deceased stems. This time-consuming process was prone to errors and could be challenging in difficult terrain or inaccessible locations.

But now with the Phantom 4 V2 drone, this task can be accomplished with relative ease. These state-of-the-art methods help showcase the success of planting projects, demonstrating to funders that we’re achieving good results and (hopefully) attracting future opportunities for further plantings.

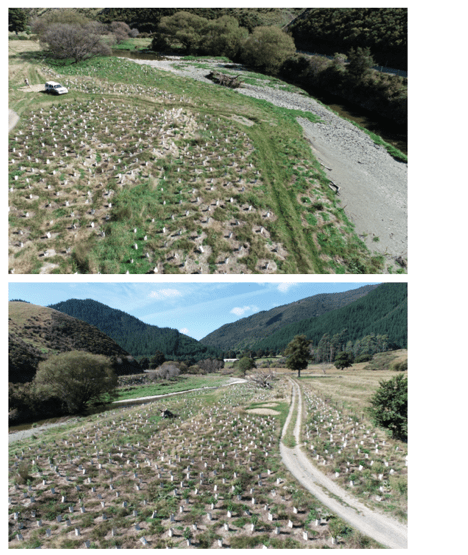

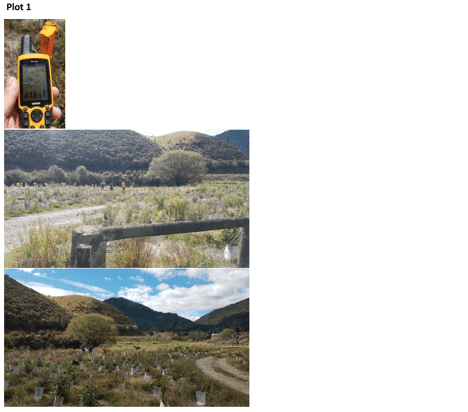

Having an accurate record of pant growth at a site also gives a good feel for progress. When taking a photo from the ground it can be difficult to consistently find the same spot. Plants can grow quickly, obscuring the view. From the air, however, a GPS point can effortlessly replicate a photo spot. This is invaluable for plot surveys of planting sites and for mapping plant regeneration over time.

Who’s the drone pilot?

Craig Allen heads up TET’s evaluation and monitoring programme. After finishing undergraduate studies at Otago, he completed a Masters degree in wetland hydrology. For the last 15 years Craig has worked as a freshwater scientist in roles that evolved into specialist work in hydrology, freshwater ecology and GIS mapping.

Josh Foster from MPI kindly donated two days of his time to train Craig and Elliot Easton (project manager for Restoring the Moutere) on everything you need to know about flying a drone. The introduction was comprehensive and necessary, as neither Craig nor Elliot had any previous experience.

After familiarising themselves with the rules and regulations from CAA and NZ Aviation Security Service, the drone was ready for its maiden flight.

“It’s very cool to fly,” says Craig. “It’s so manoeuvrable and, once you get a feel for the direction and speed, it’s not hard.

“It also has a setting where you can pre-programme a survey and the drone will fly itself across a site taking photos. When back in the office you run the photos through software that converts it to a ‘photo mosaic image’ which you can then insert onto a map.”

Each year Craig will take another photo, so he’ll eventually be able to flick through and look at multi-year growth at a particular site. A clear comparison with ‘before and after’ images can visually demonstrate the transition from seedling to closed canopy.

Image processing

Craig says flying the drone is the quick and easy part. It’s when he gets back to the office that the work starts.

The images need to be uploaded as jpeg files to ArcGIS Online first, and then moved into the Webmap that TET uses to manage the project. This software allows for base map layers to be altered and filtered to suit the end requirement—topographic, satellite or otherwise.

“Fifteen minutes to fly, then two hours to process!” says Craig. “The quality of the images is really amazing. It turns a blurry, grainy Google Maps photo into a sharp image—where it’s possible to zoom in to such a level of detail that you can see if the plant guard is still in good condition or not.”

Dodgy moments?

Craig has found the drone has its limits, but thankfully without disaster.

“Usually there are objects in the way,” he says. “I was flying out at Wakapuaka once and had just finished doing an automated survey —where the drone flies itself to a pre-set grid to make a map.

“When it came to return home there was a hill with a tree sticking up…. I was worried it would just fly straight into it, but luckily the drone has safety features that are smarter than I am and could sense upcoming objects before collision, so it stopped in time.”

Healthy plants, healthy water, healthy people

The drone has certainly made Craig’s job easier and given greater detail to the data he can collect. “It’s such a good tool to have in this work space,” he says. “Its going to be one of those things that we’ll look back [on] and say, ‘I can’t believe we tried to do that stuff without a drone’.

“And it’s good flying practice for me to chase my kids around the park!”