The fourth bi-annual Banded Rail survey took place on a sunny September Sunday morning on the shores of the Waimea Inlet. Some volunteers wore gumboots, others opted for sneakers. All were eager to get stuck into the survey transects and spy the elusive Banded Rail. Like detectives, we were hunting for clues to their whereabouts and footprints in the estuarine muds were the evidence.

Battle for the Banded Rail

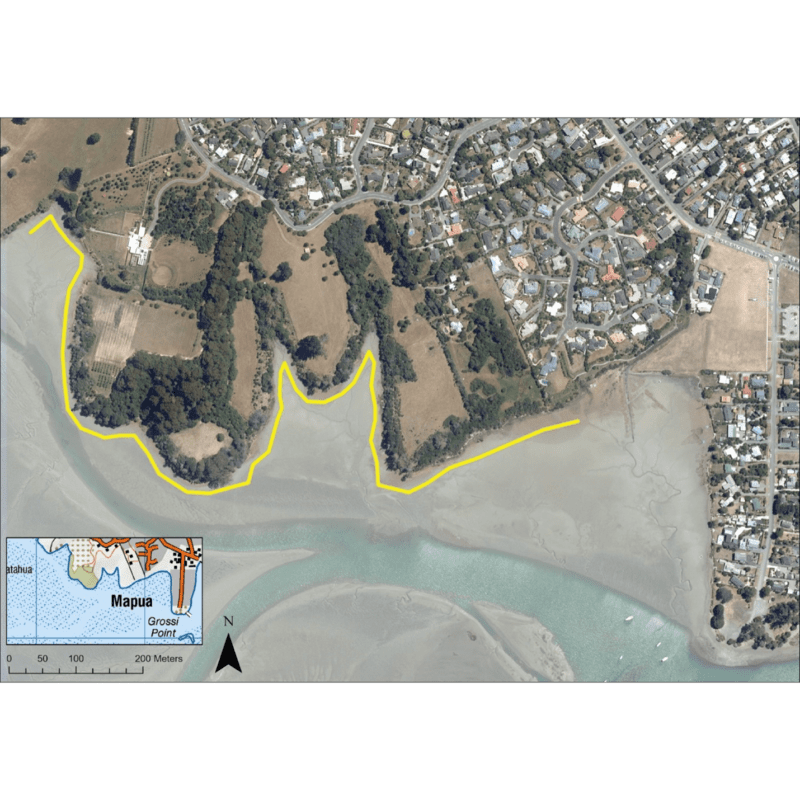

Battle for the Banded Rail is working with local communities to restore thriving birdlife to the Waimea Inlet by trapping introduced predators and restoring habitat around the estuary margin. Since 2015, thanks to 1,000s of volunteer hours, over 50,000 native plants have enhanced the inlet and over 1,000 traps now cover 50 km of banded rail habitat. Nearly 9,000 predators have been trapped.

But how do we know all this good mahi is paying off? That’s where the bi-annual survey comes in.

Image credit: Bradley Shields

A hurried scurry – Banded Rail

Most wetland bird species like Banded Rail are notoriously difficult to detect, with their camouflaged plumage, tendency for concealment in wetland vegetation and secretive habits. But such headwinds do not deter the avid volunteers who trapse through the muddy saltmarshes, searching for signs.

You would likely think they were weka given their gait and hurried scurrying for the rushes. In Nelson/Marlborough their range is limited to large areas of salt marshes in the upper tidal zone, with a population estimate of around 20 pairs. They seldom venture into the open, usually at dawn and dusk.

The survey

Three previous surveys have been conducted in 2014, 2016 and 2018. The parameters for survey day are quite strict – a non-rainy day with a low tide in the early morning on a weekend when volunteers are available.

The project is fortunate to have the expertise of ornithologist Graeme Elliot to oversee the survey. Graeme has been studying Banded Rail since the 1980s and there is no-one in New Zealand with more experience in Banded Rail, especially as he grew up on the shores of the inlet and used to observe them as a youth. Graeme hopes the trapping and planting programmes will increase populations in all the embayments of the Waimea.

We listened intently as Graeme explained how they forage. “If you come across some footprints in the open that you think might belong to rails, follow them – if they’re Rails they will eventually go into the rushes. And one final note: Banded Rails have distinctive droppings. They are often pinkish brown and are always gritty because they contain bits of snail and crab.”

And sure enough after a few minutes we all stopped, enthralled by a positive footprint sighting and now feeling confident to tell our Rails from our Stilts.

“Banded Rails are hard to see – they don’t fly much and they sneak around in the rushes. The best way to tell if they’re around is to look for their footprints”.

Graeme Elliot, ornithologist

NMIT trainee rangers on the loose

The survey party included two trainee NMIT Rangers. Kirsten Booker heard about the survey at the morning tea break at one of the volunteer plantings and signed up. The Banded Rail survey was a neat fit with her course, as a data management project formed a component.

“Being grouped with Graeme enhanced our excitement and determination. When we started to find the prints it was really interesting to see where they came from and where they were going, trying to work out if they were the same bird or a different bird in the same area,” says Kirsten.

“The main highlight was probably when Graeme pulled out his binoculars and we watched a Banded Rail – the creature whose footprints we had been searching for. It really gave us a sense of why we were doing this.”

Kirsten Booker, Trainee NMIT Ranger

Avian detectives become muddy buddies

Project leader, Kathryn Brownlie gave a safety briefing – stay in pairs, let her know when we were out safe, be off the water before the tide comes in. And just in case we got stuck, fall to the ground and roll over. It was a cursory comment, which could have gotten lost in the excitement, but it somehow stuck.

I was paired with experienced surveyor, Anne Hilson. After we dropped one vehicle at the finish point, we drove together to a grassy strip alongside a flax swamp. Glad of the Red Bands and noting how wet it was underfoot, we descended a bank to the inlet edge. Where were those footprints?

The serene bay housed plenty of mud snails, Pukeko foraging on the grassy margins and a wide strip of rushes where Banded Rail could feed. But the only footprints were ours. And it was these human footprints that started to cause concern. With every pace the depth of gumboot penetration into the mud was getting deeper and the effort required to lift our feet out was getting greater. Before we had time to change course, we were stuck!

Anne, a fit and able woman, but with weakened knees from a lifetime of adventure, was struggling to remove herself from the sticky mud. I moved closer to help, leaning over to grab the top of her boots and supply the added strength to extract her suctioned feet. By now Anne was sinking and every movement only deepened our troubles. My hands slipped and I fell over on my backside, mud splatters coating my clothing. Was this the time to take Kathryn’s advice and roll over? One last effort, now embracing the mud (our new catchphrase) and with satisfying squelches out popped one foot and then the other.

With appearances more resembling mud wrestlers than field surveyors, we gingerly chose a safer route on the firmer gravels. Our bonding experience with both mud and each other primed our senses for the search, but with the incoming tide, it was only our footprints that were covered.

Some weird stares came my way at the veggie shop. But knowing I had done my bit for Banded Rail trumped the awkwardness. Next survey, I’ll be in full overalls and with shoes taped to my feet.